Hanrahan v Revenue: Tax Avoidance and the GAAR

Tuesday, 16 September 2025

This article was first published in the Issue 2, 2025 of the Irish Tax Review.

Introduction

In Dermot Hanrahan v Revenue Commissioners [2024] IECA 113 the Court of Appeal considered the application of the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) in s811 of the Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 (TCA 1997) to a scheme related to capital gains tax (CGT). The Court of Appeal held that s811 applied to the scheme, reversing the judgment of the High Court and restoring the first-instance decision of the Tax Appeals Commission. Section 811 has now been replaced by s811C TCA 1997 in relation to transactions commenced after 23 October 2014, but the decision remains of relevance, given that s811C is closely modelled on its predecessor.

The Court of Appeal also made important findings on the approach to statutory interpretation of taxing provisions and when a taxpayer’s return will contain “a full and true disclosure of all material facts necessary for the making of an assessment” for the purposes of s955(2) TCA 1997, which determined the time limits in which Revenue may amend an assessment.

Relevant Issues

The Appeal Commissioner stated eight questions of law for the opinion of the High Court, but the High Court conveniently grouped those questions into three general issues, and this approach was followed by the Court of Appeal:

- Was the Notice of Opinion issued by Revenue under s811 TCA 1997 out of time by reason of s955(2) TCA 1997 (“the time limit issue”)?

- Was the transaction entered into by the taxpayer a “tax avoidance transaction” within the meaning of s811 TCA 1997 (“the substantive issue”)?

- Was the Notice of Opinion void by reason of an error in the description of the component parts of the transaction (“the invalidity issue")?

The Appeal Commissioner had found in favour of Revenue on all of these issues. The High Court agreed with the Appeal Commissioner on the time limit and invalidity issues but found in favour of the taxpayer on the substantive issue.

The Transaction and CGT Consequences

The Court of Appeal (Donnelly J and Butler J) described the taxpayer’s arrangements at issue as:

“an elaborate set of financial transactions, for which the taxpayer never provided any evidence of a commercial or business purpose and which were entered into for the purpose of ensuring the taxpayer gained maximum relief from Capital Gains Tax”.

The overall result of the arrangements was that a significant tax loss for CGT purposes was purportedly created owing to the operation of the connected-party rules, even though no corresponding commercial loss had been suffered.

The alleged tax-avoidance transaction was a complex scheme involving a number of companies and consisted of the following elements (collectively, “the Transaction”):

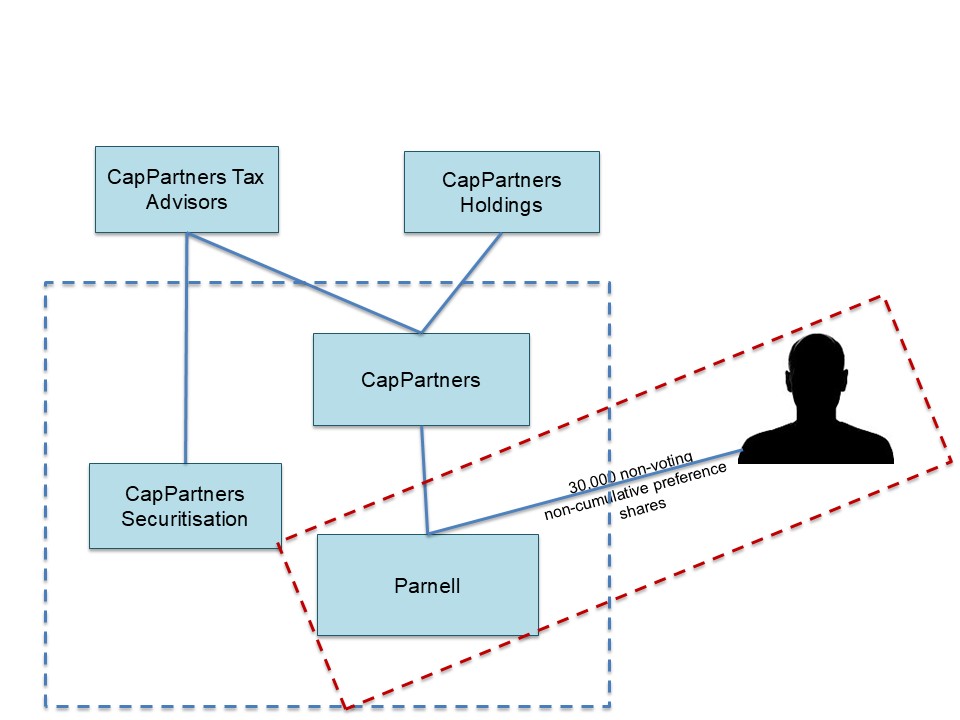

(a) The beneficial interest in the issued share capital of CapPartners (“CapPartners”) was held by CapPartners Tax Advisors and CapPartners Holdings Limited.

(b) The beneficial interest in the issued share capital in CapPartners Securitisation (“Securitisation”) was held by CapPartners Tax Advisors.

(c) CapPartners Parnell Investments Limited (“Parnell”) was formed on 2 June 2004, with CapPartners holding a single share, entitling it to all voting rights. As a consequence, CapPartners, Securitisation and Parnell were commonly owned and connected pursuant to s10 and s432 TCA 1997.

(d) On 25 August 2004 Dermot Hanrahan acquired 30,000 non-voting, non- cumulative preference shares of €1 each in Parnell. As a result, Mr Hanrahan was connected with Parnell pursuant to s10 and s432 TCA 1997.

Fig. 1: Relationships between the parties in Hanrahan case.

The relationships between the parties are shown above. The dotted lines show the connected parties for tax purposes.

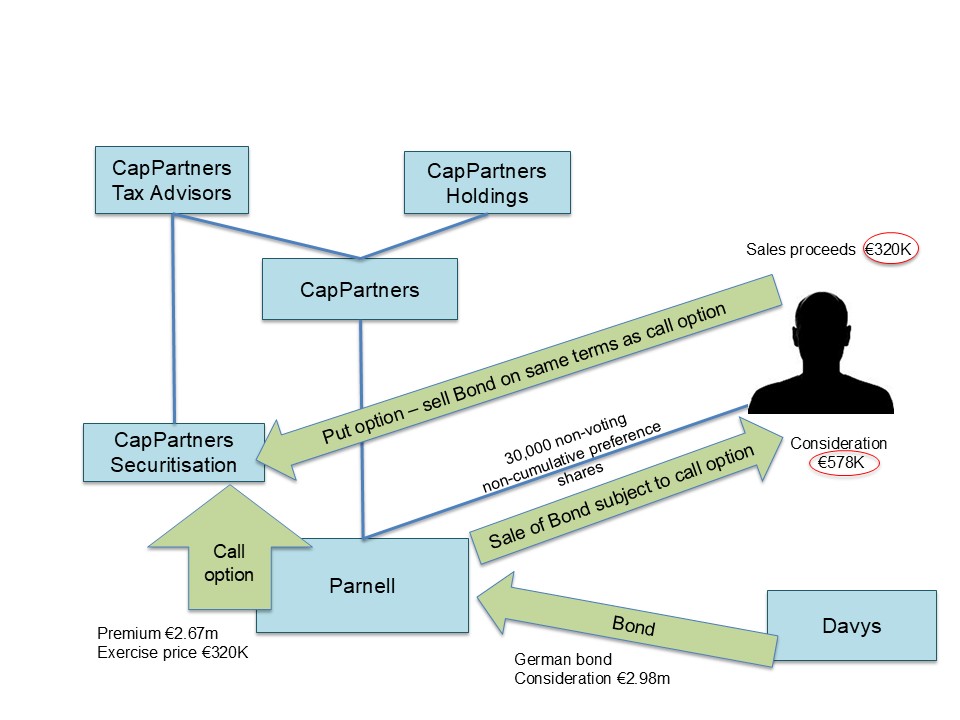

(e) On 7 October 2004 Parnell purchased a German government bond (the “Bond”) with a nominal value of €2.94m for consideration of €2.98m from a third party.

(f) By a call option agreement dated 7 October 2004, Parnell granted a call option to Securitisation for a premium of €2.67m, entitling Securitisation to purchase the Bond for an exercise price of €320K.

(g) By a bond purchase agreement dated 7 October 2004 between Parnell, Securitisation and Dermot Hanrahan (the “BPA”), Parnell undertook to sell the Bond to Mr Hanrahan for €578K, subject to the call option agreement in favour of Securitisation. Under the BPA, Securitisation also granted a put option to Mr Hanrahan to sell the Bond to Securitisation on the same terms as under the call option agreement.

(h) On 7 October 2004 Mr Hanrahan acquired the Bond (with a nominal value of €2.94m) from Parnell for €578K pursuant to the terms of the BPA, financed by an interest-free loan of €280K provided by Parnell and the remainder from his own resources.

(i) Pursuant to the BPA, on 22 October 2004 Mr Hanrahan exercised his put option, requiring Securitisation to purchase the Bond from him for €320K.

Fig 2: Transactions in Hanrahan case.

These transactions are shown below. The relevant CGT provisions in TCA 1997 are as follows:

- Section 547(1) provides that a person’s acquisition of an asset for CGT purposes is deemed to be for a consideration equal to the market value of the asset where it is acquired otherwise than by way of a bargain made at arm’s length. Section 549(2) provides that where a person acquires an asset from a connected person, the acquisition shall be treated as made otherwise than by way of a bargain at arm’s length.

- However, under s549(6) and (7), where an asset is subject to an option or other right to acquire the asset that is enforceable by the person making the disposal or by a person connected with them, the market value of the asset is determined as if the option or other right did not exist.

- Section 31 provides that allowable losses may be deducted from chargeable gains in determining the CGT due in a year of assessment, and s546 provides, broadly, that the allowable loss accruing on a disposal of an asset is computed in the same way as the amount of a gain.

The CGT consequences of the Transaction were therefore as follows:

- The sale of the Bond by Parnell to Mr Hanrahan was a transaction between connected persons and was therefore deemed to be for a consideration equal to its market value under s547 and s549(2) TCA 1997, even though Mr Hanrahan paid only €578K to purchase the Bond.

- Although the Bond was subject to a call option in favour of Securitisation, the market value of the Bond for these purposes was calculated as if the call option did not exist, given s549(6) and (7). This meant that Mr Hanrahan was deemed to purchase the Bond for an acquisition cost equal to its deemed market value of €2.98m.

- Having acquired the Bond from Parnell for €578K, which he sold to Securitisation for €320K, Mr Hanrahan made an actual loss of €258K. However, given that he was deemed to have acquired the Bond for €2.98m, the combined effect of s31, s547 and s549 TCA 1997 was that he made a CGT loss of €2.66m (i.e. €2.98m less the consideration received of €320K).

Revenue accepted that this was the correct application of the CGT rules in the absence of s811 TCA 1997, but in December 2009 it issued a Notice of Opinion under s811 to Mr Hanrahan which sought to deny this loss.

Section 811 TCA 1997

The Court of Appeal provided a useful definition of “tax avoidance” and its view of what s811 is trying to achieve:

“It is possible, quite legally, to avoid paying tax on an income or gain. Avoidance of tax occurs where provisions of the tax code are exploited to the fullest extent permitted by their terms to ensure that a taxpayer pays either no tax or the least possible amount of tax. Skilful tax practitioners spend considerable energy setting up elaborate schemes for the purpose of reducing, in a legally compliant manner, the tax a taxpayer will ultimately have to pay. The State, through the tax code, has sought to reduce tax avoidance by use of either specific tax avoidance sections or, by introducing, for the first time…a general tax avoidance provision.”

Section 811 TCA 1997 is a complex provision. O’Donnell J described its predecessor as “a provision of mind-numbing complexity” (Revenue Commissioners v O’Flynn Construction Limited [2013] 3 IR 533). However, it can be broken down into a number of sequential tests. Section 811 applies to a “tax avoidance transaction”, which is defined by s811(2) as follows:

“a transaction shall be a “tax avoidance transaction” if having regard to any one or more of the following –

(a) the results of the transaction,

(b) its use as a means of achieving those results, and

(c) any other means by which the results or any part of the results could have been achieved,

the Revenue Commissioners form the opinion that –

(i) the transaction gives rise to, or but for this section would give rise to, a tax advantage, and

(ii) the transaction was not undertaken or arranged primarily for purposes other than to give rise to a tax advantage.”

For these purposes, “tax advantage” includes:

“a reduction, avoidance or deferral of any charge or assessment to tax…arising out of or by reason of a transaction, including a transaction where another transaction would not have been undertaken or arranged to achieve the results, or any part of the results, achieved or intended to be achieved by the transaction”.

Section 811(3)(a) then provides that Revenue shall not regard the transaction as being a tax avoidance transaction if it is satisfied that:

“(i) notwithstanding that the purpose or purposes of the transaction could have been achieved by some other transaction which would have given rise to a greater amount of tax being payable by the person, the transaction –

(I) was undertaken or arranged by a person with a view, directly or indirectly, to the realisation of profits in the course of the business activities of a business carried on by the person, and

(II) was not undertaken or arranged primarily to give rise to a tax advantage,

or

(ii) the transaction was undertaken or arranged for the purpose of obtaining the benefit of any relief, allowance or other abatement provided by any provision of the Acts and that the transaction would not result directly or indirectly in a misuse of the provision or an abuse of the provision having regard to the purposes for which it was provided.”

Section 811(3)(b) provides that in forming an opinion under s811(3)(a) in relation to any transaction Revenue shall have regard to:

“(i) the form of that transaction,

(ii) the substance of that transaction,

(iii) the substance of any other transaction or transactions which that transaction may reasonably be regarded as being directly or indirectly related to or connected with, and

(iv) the final outcome and result of that transaction and any combination of those other transactions which are so related or connected.”

Under s811(4) Revenue may “at any time” form the opinion that any transaction is a tax avoidance transaction and calculate the tax advantage that it considers arises from the transaction. Upon forming this opinion, it must, under s811(6), issue a Notice of Opinion to the taxpayer concerned setting out details of the alleged tax avoidance transaction and tax advantage obtained. Where Revenue’s opinion that a transaction is a tax avoidance transaction becomes final and conclusive, under s811(5) it may make all such adjustments as are just and reasonable (including denying any deduction or loss) in order that the tax advantage is withdrawn.

Time Limit Issue

In general, s955(1) TCA 1997 provided that Revenue could amend an assessment made by a chargeable person “at any time”. However, s955(2) provided an important limitation on this: where a person has delivered a return that contains a “full and true disclosure of all material facts necessary for the making of an assessment for the chargeable period”, Revenue may not make an assessment more than four years after the end of the chargeable period in which the return is delivered.

As originally enacted, s811(4) TCA 1997 provided that Revenue could form an opinion that a transaction is a tax avoidance transaction “at any time”. However, in Revenue Commissioners v Hans Droog [2016] IESC 55 the Supreme Court held that where the taxpayer had made a fully compliant return, the four-year time limit in s955(2) also applied to any additional tax payable under s811.

The Oireachtas effectively reversed Droog through s130 of the Finance Act 2012, which amended s811 by inserting a new sub-section (5A). This provided that where Revenue’s opinion that a transaction is a tax avoidance transaction under s811 becomes final and conclusive (i.e. when all appeals have been finally determined), the time limits in Part 41 TCA 1997 (including s955) do not apply to the making of an assessment or any requirement to pay tax for the purposes of giving effect to this opinion. This applied to any assessment or amended assessment made on or after 28 February 2012.

The Court of Appeal therefore had to consider:

- whether the taxpayer had made a “full and true disclosure of all material facts necessary for the making of an assessment” in his relevant returns; and

- if so, whether s811(5A) disapplied the four- year time limit in s955(2) TCA 1997.

Full and true disclosure

In his 2004 return the taxpayer failed to check the boxes indicating that the Bond had been acquired from a connected person and market value had been substituted for the cost of acquisition. The court had little hesitation in holding that this return did not include a full and true disclosure of all material facts.

The taxpayer’s 2005 return was also relevant, as the losses from the transactions occurring in 2004 had been carried forward to set against gains in 2005. The form used to complete the 2005 return did not make any express enquiry as to the nature or source of losses carried forward from preceding years. The High Court held that there was no material non-disclosure on this return.

The Court of Appeal disagreed with this, holding that full and true disclosure was required of the source of the losses, albeit that they were incurred in 2004, as this was a material fact necessary for the making of an assessment for 2005. The fact that this information could not be readily supplied by means of checking boxes on the digital form did not preclude the taxpayer from providing the information to Revenue through other means. The court left open the question of whether such disclosure would have been required for 2005 if a full and true disclosure had been made in 2004.

This meant that the four-year time limit in s955(2) TCA 1997 did not apply to either return.

Disapplication of four-year time limit

The Court of Appeal briefly addressed this issue, even though it was not strictly relevant, given the court’s conclusion on the first point. The court held that the clear legislative intent behind s811(5A) was to enable assessments to be made or amended at any time, in order to give effect to an s811 opinion that had become final and conclusive, regardless of the chargeable period to which the assessment related and whether that period pre-dated the enactment of s811(5A). The presumption against retrospective legislation was displaced because the section was clearly intended to have retrospective as well as prospective effect.

The taxpayer also argued that the retrospective effect of s811(5A) impaired his constitutionally protected rights, but the court noted that the taxpayer would need to issue separate proceedings to make this challenge.

Tax Avoidance Transactions

It was not disputed that the Transaction met the requirements of s811(2), i.e. it gave rise to a tax advantage and was not undertaken or arranged primarily for purposes other than to give rise to a tax advantage. At issue was whether the Transaction was excluded from being a “tax avoidance transaction” under s811(3)(a)(ii), i.e. as a transaction undertaken or arranged for the purpose of obtaining the benefit of a “relief, allowance or abatement” provided by TCA 1997 (the deduction of losses under s31) and whether it was a misuse or abuse of that provision, having regard to the purpose for which it was provided.

The Court of Appeal therefore needed to consider the purpose of s31 TCA 1997 within the statutory scheme of the CGT provisions and whether the provision had been misused or abused by the taxpayer.

In the High Court, Stack J regarded s549 TCA 1997 as an anti-avoidance provision. She said that the deemed market-value acquisition cost of the Bond, which operated to create the artificial loss, arose because of the operation of this anti-avoidance provision. She held that where there is a specific anti- avoidance provision in place that governs the transaction under consideration, a general anti-avoidance provision such as s811 could not apply, as this would exceed the proper constitutional role of the courts. In addition, the purpose of s31 (which was to relieve losses computed under the CGT rules) should not be interpreted in light of s549. In effect, the taxpayer was able to avoid the anti-tax- avoidance provisions and take advantage of them to create the very artificial loss that they were designed to prevent.

Statutory interpretation

The Court of Appeal made some helpful observations on the principles applicable to the interpretation of taxation statutes. In Heather Hill Management Company CLG v An Bord Pleanála [2022] IESC 43 the Supreme Court (per Murray J) highlighted how the identification of the purpose of legislation plays a role in the interpretation of all statutes. This developed the approach set out by the Supreme Court in its earlier decision in Bookfinders Ltd v Revenue Commissioners [2020] IESC 60. In an important passage in Heather Hill (para. 116) Murray J summarised the limits of a purposive approach to construction:

“the Oireachtas usually enacts a composite statute, not a collection of disassociated provisions, and it does so in a pre-existing context and for a purpose. The best guide to that purpose, for this very reason, is the language of the statute read as a whole, but sometimes that necessarily falls to be understood and informed by reliable and identifiable background information…However – and in resolving this appeal this is the key and critical point -– the ‘context’ that is deployed to that end and ‘purpose’ so identified must be clear and specific and, where wielded to displace the apparently clear language of a provision, must be decisively probative of an alternative construction that is itself capable of being accommodated within the statutory language.”

The Court of Appeal therefore observed that not only does s811 direct Revenue and the courts to have regard to the purpose of the provisions at issue, but context and purpose are relevant to interpreting tax statutes even in a more general manner.

In O’Flynn Construction, the leading authority on the GAAR, the Supreme Court considered a scheme intended to obtain the benefit of export sales relief by a non-exporting company, where the transaction at issue was said to be “highly artificial and contrived”. O’Donnell J, giving judgment for the majority, set out the approach to determining the purpose of a relieving provision and whether it has been misused or abused, under what is now s811(3)(a)(ii) (para. 77):

“In other cases the provision may be so technical and detailed so that no more broad or general purpose can be detected, or may have its own explicit anti-avoidance provision. In such a case there may be no room for the application of s. 86 since it may not be possible to detect a purpose for the provision other than the basic one that the Oireachtas intended that any transaction which met requirements of the section should receive the relief. However, there are some cases, of which this is one, where it may be possible to say with some confidence that, though there has been compliance with the literal words of the statute, the result is not the sort of relief that the Act intended should result. In such cases, s. 86 permits an evaluation of the particular transaction and a consideration as to whether it comes not just within the words, but also within the intended scheme, or is rather a misuse or abuse of it.”

The Court of Appeal held that, whatever the normal approach of the courts to statutory interpretation, it was clear that s811 provided a statutory imperative to go beyond this and consider the purpose of the relevant provisions. Therefore, even a relief arising from a transaction that complies with the words of a statute may be disallowed as a misuse or abuse of its provisions.

Does s811 apply where there is specific anti- avoidance legislation?

The Court of Appeal held that the High Court decision was wrong on this point. The fact that there is specific anti-avoidance legislation does not preclude the operation of s811. Section 811 is a general provision that is intended to apply to any transaction undertaken or arranged to benefit from any relief, allowance or abatement.

Identification of purpose

The Court of Appeal held that s811(3)(a)(ii) required a specific consideration of the purpose of each relevant legislative provision, which is understood by looking at the words used in their context, having regard to the legal background against which the provision was enacted.

The purpose of s31 therefore had to be viewed in the context of the wider CGT provisions in TCA 1997, including the deeming provisions in s549. The court said that the purpose of s549 was to combat tax avoidance by preventing connected persons manipulating the CGT provisions by the disposal of assets at an undervalue or by exploiting the CGT provisions to overvalue losses or undervalue gains. The purpose of s31 was to relieve financial loss against financial gain, and allowable losses were intended to be actual or real financial losses.

The court acknowledged that the exercise conducted under s811 was different from the consideration of purpose as part of the ordinary principles of statutory interpretation laid down in Bookfinders and Heather Hill, because s811 permits examination of the form, substance and outcome of the transaction. In the absence of s811 there would be a mechanical application of the tax code, including the s549 deeming provisions, to each of the steps taken in isolation. However, s811 gave Revenue “a completely different dissection kit with which to examine the Transaction”.

In the court’s view, the Transaction was “undoubtedly” undertaken or arranged for the purpose of taking advantage of the relief under s31 through the use of the deeming provisions of s549. The purpose of s31 had to be considered in the context of the provisions of TCA 1997, including those of the “interlocking” s549.

The court noted that under s811(3)(a)(ii) it had to consider whether the Transaction would “result directly or indirectly in a misuse of the provision or an abuse of the provision having regard to the purposes for which it was provided [emphasis added]”. The words “directly or indirectly” illuminated the comprehensive nature of the sub-section and reinforced its conclusion that the purpose of s549 must be considered when addressing the purpose of s31.

The court therefore held that there was a clear misuse of s31 by the Transaction (para. 148):

“Its sole purpose was to manipulate, and thereby misuse and abuse, the provisions of s. 549 concerning connected persons for the purposes of constructing ‘an artificial loss’. This was truly an ‘artificial loss’ because it made use of the deeming provisions to generate a loss for the sole purpose of avoiding tax. That is a clear misuse of s. 549 which results directly or indirectly in a clear misuse of s. 31 provisions...Put simply, this Transaction, which was carried out solely for the purpose of avoiding tax, exploited the anti-avoidance provisions of s. 549 and thus misused and abused the purpose of that provision.”

Validity of Notice of Opinion

The taxpayer argued that Revenue’s Notice of Opinion was invalid as it contained an error in the description of the Transaction. The notice recited that a put option in respect of the Bond was granted by Securitisation to Parnell, when in fact the put option was granted by Securitisation to the taxpayer directly (see step (g) above).

The Court of Appeal considered that this error was not material, as the element of the Transaction that was misdescribed (the grantee of the put option) was not a matter that fed into the tax consequences of the transaction nor its nature as a tax avoidance transaction. The key factors that made the Transaction a tax avoidance transaction (the connection between the parties and the consequent substitution of market value for the price of the Bond) had been sufficiently set out in the Notice of Opinion. The court therefore decided that the notice was valid.

However, the court rejected Revenue’s argument that the taxpayer should be regarded as having notice of the correct details of the transaction because he was a participant in it, which it criticised as “Kafkaesque”. Revenue’s argument that any error in the Notice of Opinion could be cured because the correct description was included in prior Revenue correspondence was looked on more favourably but not considered further, given the court’s finding on the validity of the notice. The court also stated that, if it were necessary to do so, it would exercise the High Court’s power to formally amend the Notice of Opinion to correct the error.

Outcome

The final outcome was that Revenue succeeded on all issues – Revenue’s Notice of Opinion was valid; it was issued within the applicable time limit; and the Transaction was a tax avoidance transaction that could be defeated by s811 TCA 1997.

Commentary

The Court of Appeal has provided helpful guidance on the interpretation and application of s811. This will be useful to practitioners, given that the last significant judicial consideration of the GAAR was in O’Flynn Construction in 2011, although a number of questions remain.

As in O’Flynn, Hanrahan focusses on whether there was a misuse or abuse of a relieving provision, having regard to the purposes for which it was provided. This means that there remains limited judicial guidance on the tests in s811(2), i.e. when a transaction gives rise to a tax advantage, or when a transaction is undertaken or arranged primarily for purposes other than to give rise to a tax advantage.

Revenue will, no doubt, be pleased with the outcome here – the High Court decision that specific anti-avoidance legislation precluded the operation of s811 placed a significant limitation on the operation of the GAAR. This was, arguably, based on obiter dicta in O’Flynn that had been taken out of context.

The Court of Appeal decided the case on the basis that s31 TCA 1997 was a relieving provision and was abused indirectly in light of its purpose when considered together with s549 TCA 1997. However, this could have been reasoned differently, as s549 also uplifted the taxpayer’s base cost and so, to that extent, was in itself a relieving provision. The taxpayer exploited an exception in s549 to obtain a base cost uplift that actually exceeded the market value of the Bond. Provisions such as s549 may be relieving or taxing, depending on the context and circumstances, which suggests that an a priori classification of particular provisions as relieving provisions or anti-avoidance provisions may not be appropriate. Arguably, this is what led the High Court astray.

Purpose of relieving provisions

The Court of Appeal held that the purpose of s31 TCA 1997 was to give relief for real and tangible losses. However, this conclusion seems open to debate. The CGT provisions in TCA 1997 are replete with fictions and artificiality; CGT is a very prescriptive tax with many deeming provisions. Section 31 gives relief for allowable losses which, by s546, are to be computed using the same detailed rules (including deeming provisions) as gains. The non-economic loss here effectively arose from the interaction of two artificial deeming provisions.

The Court of Appeal also took a rather one- sided view of the purpose of s549. This section contains an inherent symmetry – while the purchaser will benefit from an uplifted base cost, the seller will usually have been taxed on an uplifted gain. The beneficiary of s549 will depend on the market value of the asset disposed of relative to the actual consideration paid. There may be cases where the operation of the deeming provisions equally means that real and tangible losses are disallowed or converted into gains. Arguably, this was a case where, as O’Donnell J said in O’Flynn Construction, a “provision may be so technical and detailed so that no more broad or general purpose can be detected”.

There remains some uncertainty as to how Revenue should determine the “purpose” of a relieving provision under s811(3)(a)(ii). The Court of Appeal started with a consideration of the purpose and context of a provision as part of the ordinary canons of statutory interpretation as laid down in Heather Hill. However, as the court itself acknowledged, if the normal rules of interpretation can defeat a scheme, there is no need to apply s811. The “purpose” of a provision under s811(3)(a)(ii) must therefore have a wider meaning, or s811(3)(a) would effectively be devoid of application. It seems that the Court of Appeal was willing to go beyond the normal rules of construction to consider the wider or overarching purpose of s31 (it should apply only to real and tangible losses), but it is not clear how this would be ascertained in other cases. The court also said that there should be a specific consideration of the purpose of each relevant legislative provision and cautioned against applying generalised expressions of purpose.

Taxpayer’s purpose

Although the Court of Appeal focussed on the “purpose” of a relieving provision under s811(3)(a)(ii), the taxpayer’s purposes in entering into a transaction are also of vital importance under the GAAR. A transaction will not be a “tax avoidance transaction” if it was undertaken or arranged primarily for purposes other than to give rise to a tax advantage.

In Hanrahan it appeared that the scheme had no commercial purpose other than to generate an artificial loss. As in O’Flynn Construction, it was an entirely contrived and tax-driven scheme. The taxpayer’s purposes in entering the scheme were therefore not considered in any detail. This means that the Irish courts have not yet had to consider whether the GAAR could apply if arrangements have an overall commercial purpose but part of the structure is a “tax avoidance transaction”. In this case should you look at the purpose of the overall scheme or the individual steps, and should the purpose of other participants in the scheme also be considered? And how much tax structuring is permitted where there is an overall commercial purpose? One of the matters to be taken into account in determining whether a transaction is a “tax avoidance transaction” is “any other means by which the results or any part of the results [of the transaction] could have been achieved”, which suggests that Revenue may contrast the tax effects of a hypothetical alternative transaction the taxpayer could have entered into instead.

These difficult issues have been considered by the UK courts in the context of specific anti- avoidance provisions that deny a tax benefit if one of the “main purposes” of a scheme is to obtain a tax advantage or avoid a liability to tax (1). Some of these cases are referred to in Revenue’s Tax and Duty Manual Part 33-01- 01 on “Main purpose tests” and could inform the Irish position when an appropriate case reaches the courts. Similar “main purpose” tests are found in the Irish tax code (e.g. in s586 TCA 1997 and s41(2) of the Stamp Duties Consolidation Act 1999) and have been considered by the Tax Appeals Commission (2).

Interpretation of taxation statutes

More generally, it is helpful that the Court of Appeal recognised that the purposive and contextual approach to statutory interpretation discussed in Heather Hill may apply to tax statutes. However, although the Court of Appeal placed considerable reliance on Heather Hill, it is important to bear in mind that it is not a tax case. As the Supreme Court recognised in Bookfinders, slightly different rules apply when considering a tax provision. If after the application of all the normal rules of interpretation (including the context of the legislation) a doubt or ambiguity remains, the wording should normally be construed strictly in favour of the taxpayer, under the rule against doubtful penalisation (Bookfinders para. 52). It has also been held that exemption from tax must, similarly, be given expressly and in clear and unambiguous terms (Revenue Commissioners v Doorley [1933] IR 750 and Perrigo Pharma International DAC v McNamara [2020] IEHC 552, para. 74).

Section 811C

With effect for transactions commenced on after 23 October 2014, s811 has been replaced by s811C TCA 1997. There are subtle but important differences between the two provisions. In particular, s811 provided that a transaction would be a “tax avoidance transaction” if Revenue forms the opinion, having regard to certain matters, that the transaction gives rise to a tax advantage and was not undertaken or arranged primarily for purposes other than to give rise to a tax advantage. In contrast, a transaction is a “tax avoidance transaction” under s811C(2) if “it would be reasonable to consider that” these requirements are met. This suggests that Revenue does not need to establish the subjective purposes of the taxpayer, but only that objectively it would be reasonable to consider that a transaction gives rise to a tax advantage and is not arranged primarily for non-tax purposes.

The enforcement mechanism has also changed. Revenue is no longer required to issue a Notice of Opinion, and instead compliance with the GAAR forms part of a taxpayer’s normal self- assessment obligations.

These changes widen the scope of the GAAR, although it does not appear that they would have any impact on the outcome in Hanrahan.

There are now also separate specific anti- avoidance provisions (s549(7A) and s546A TCA 1997) that could defeat the scheme used in Hanrahan, although these are outside the scope of this article.

Comparison with UK position

In O’Flynn Construction the Supreme Court acknowledged that the predecessor to s811 (s86 of the Finance Act 1989) was enacted in response to the decision in McGrath v McDermott [1988] IR 258. In McGrath the Supreme Court rejected the doctrine of “fiscal nullity” that had been developed in the UK courts in cases such as WT Ramsay Ltd v Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1982] AC 300, under which certain steps of a transaction that were legally valid but devoid of commercial purpose could be ignored for fiscal purposes.

The Court of Appeal sought to distinguish the Irish approach from the approach of the UK courts to tax avoidance as set out in cases such as Ramsay. However, in the intervening forty- year period the UK courts have significantly developed the Ramsay approach. Since at least the decision of the House of Lords in Barclays Mercantile Business Finance Ltd v Mawson [2004] UKHL 51 (“BMBF”) it is now regarded as a principle of purposive construction of tax statutes rather than a separate doctrine of “fiscal nullity”. It applies where the relevant statutory provisions, construed purposively, are intended to apply to the transaction, viewed realistically (3).

Notably, O’Donnell J cited BMBF in O’Flynn Construction to support the application of a purposive approach. The modern UK Ramsay approach has some similarities to the modern approach of the Irish courts to purposive interpretation as laid down in Heather Hill and now Hanrahan. Even though the UK now has its own GAAR, the Ramsay approach continues to develop alongside it. It is therefore possible that UK case law could inform the approach of the Irish courts to consideration of the “purpose” of statutory provisions under the GAAR. In particular, the UK courts have given extensive consideration to when a provision may be so technical and detailed that a purposive interpretation is not possible.

Time limits and s955(2) TCA 1997

The Court of Appeal made it clear that the obligation to provide “full and true disclosure of all material facts necessary for the making of an assessment” goes beyond simply ticking the boxes and responding to direct questions on the standard return; taxpayers are also required to provide information to Revenue by other means where this is relevant to their tax liability and Revenue’s decision to assess in a particular period.

The Court of Appeal did not consider the meaning of the expression “full and true disclosure of all material facts” in detail, but this was addressed by the High Court in two judgments in 2024: Revenue Commissioners v Tobin [2024] IEHC 196 and O’Sullivan v Revenue Commissioners [2024] IEHC 611. These judgments held that the test in s955(2) is an objective one and “prima facie, if a relevant fact is not disclosed, for whatever reason, the return is not true” (para. 46 of Tobin; emphasis in original) and that “the words ‘full and true’ equates with ‘accurate’ and ‘correct’ which is appropriate in circumstances where the system is one of self-assessment” (para. 90 of O’Sullivan). This suggests that a tax return must be accurate in every material respect before it contains a “full and true disclosure of all material facts”.

However, it would seem that the requirement is limited to the disclosure of “facts” and not the potential legal or tax characterisation of transactions.

Where a transaction in one year has tax implications in subsequent chargeable periods, the requirement to disclose material facts extends to the returns for those periods. Effectively, non-disclosure in one year may infect subsequent periods. As well as the carrying forward of losses, there are a number of other situations where the facts and characterisation of a transaction could impact later periods (for example, whether an asset is acquired as trading stock or held as an investment).

Consistent with the High Court decisions in Tobin and O’Sullivan, the Court of Appeal has set a high bar for taxpayers to rely on the four- year time limit in s955(2).

Section 955(2) is part of the pre-2013 rules governing assessments and time limits in Part 41 TCA 1997. These were substantially revised in Part 41A for periods after 2012. A question arises of whether the same interpretation of the time limit provisions in Part 41A applies, given the new statutory context. Although this is outside the scope of this article, the new self-assessment rules contain a similar provision in s959AA TCA 1997, and so Hanrahan and the other decisions above are likely to remain of relevance.

Conclusion and practical implications

As practitioners, we are asked to assess the risk that a particular transaction could be challenged by Revenue under the GAAR. When tax planning arrangements are entered into, the following should be borne in mind:

- Any transaction should have a demonstrable overall commercial purpose. While the extent to which a commercially-driven transaction may include the addition of steps to achieve a favourable tax result is unclear (see above), a commercial transaction structured in a tax-efficient manner is less likely to fall foul of the GAAR. The cases where Revenue has succeeded in applying the GAAR typically involve artificial or contrived transactions that are devoid of any commercial purpose (such as Hanrahan and O’Flynn Construction).

- Particularly where a taxpayer is aiming to obtain the benefit of a relieving provision or exemption, the approach taken by the Court of Appeal suggests that they must bring themselves within the wider spirit or intendment of the relevant provision, in the context of the statutory scheme as a whole and any related provisions, and not merely within its strict terms. Coming within the overarching purpose of the relief (widely construed) will be as important as a technical parsing of the statutory language.

Following Hanrahan, it is clear that the GAAR will remain a powerful tool for Revenue in combatting tax avoidance.

Footnotes:

1. See, for example, the recent decisions of the English Court of Appeal in Kwik-Fit Group Ltd and others v HMRC [2024] EWCA Civ 434, BlackRock HoldCo 5 LLC v HMRC [2024] EWCA Civ 330 and JTI Acquisition Company v HMRC [2024] EWCA Civ 652.

2. See, for example, determination 58TACD2025.

3. See, for example, the UK Supreme Court decisions in HMRC v Tower MCashback LLP [2011] UKSC 19 and Rossendale Borough Council v Hurstwood Properties [2021] UKSC 16.

An audio version on: Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Soundcloud.

For further information please contact Lee Squires, Partner, or any member of the ByrneWallace Tax Advisors Limited team.